Monday, June 28, 2010

L'Illusionniste

From Triplets of Belleville director Sylvain Chomet! I got giddy just thinking about how amazing this is going to be! There is nothing that I want to see more this entire year.

Note: Seems like there is a really strange and emotional backstory to this, too.

Tuesday, June 15, 2010

Newcity Review: Ray Noland at The Chicago Urban Art Society

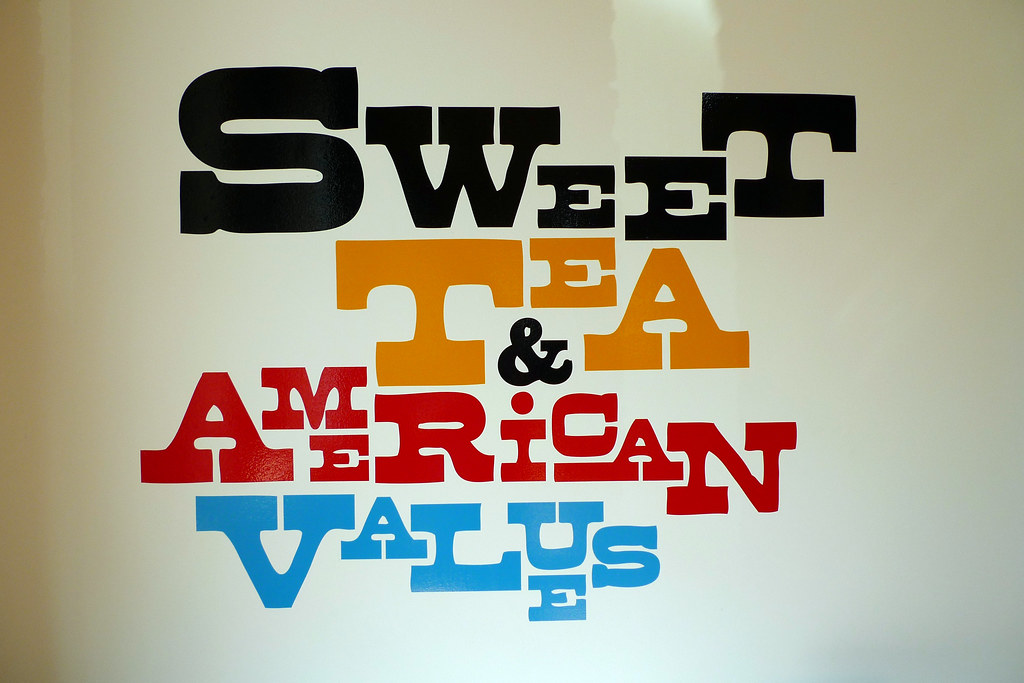

Hot off the panini press you haven't used since 2002, here's my latest review in Newcity of the Ray Noland show Sweet Tea & American Values, open now through July 30th at the Chicago Urban Art Society.

(June 14, 2010) For the time being, Ray Noland has set up camp in Pilsen, covering the walls of the cavernous Chicago Urban Art Society (CUAS) with his graphic stencils and posters. Noland’s “Sweet Tea & American Values” is the first exhibition to christen the non-profit’s new 4,200 square-foot space run by siblings Lauren Pacheco and Peter Kepha.

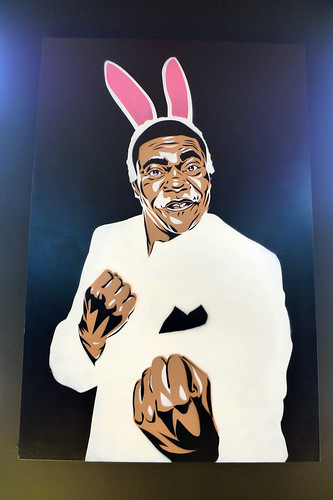

Noland’s work is unabashedly political. He skewers celebrities, musicians, politicians and assumptions about race and gender, all with equal abandon. It’s clear that Noland was working through a lot of ideas for “Sweet Tea,” riffing on old imagery, alongside new works created with the CUAS space in mind. According to the artist, almost three-quarters of the work is new (the rest is comprised of his Obama posters and the iconic “Go Tell Mama” series). With the flexibility and sense of experimentation that portends a good future for CUAS, the directors gave Noland the opportunity to work (and occasionally sleep) in the gallery for a month prior to the opening.

Unfortunately, in “Sweet Tea,” Noland’s attempt to bring the street indoors falls flat. While the installations are charming, the handful of plywood walls, plastered with faux “weathered” posters and Noland’s signature guilty, childlike Blagos, are an ineffectual spatial experiment. Bringing Blagojevich indoors also seems unnatural; that tell-tale, hand-in-the-cookie-jar expression is most powerful when it’s unexpectedly stumbled across outside. Seen outdoors, we can picture the real Blagojevich infamously jogging (or on the lam), but indoors Blago is just running in circles, and has nowhere to go. There is simply not enough of Noland’s art to fill the huge gallery space, and the street-art atmosphere seems token when paired with Noland’s more traditionally displayed works on canvas.

What works best in the space are the bold, singular, graphic works—the intricately stenciled portraits on canvas, rich with layers of flat color, and the tongue-in-cheek advertisements for No-Race Creme. Noland’s background in design is evident, for his strength lies in icons, particularly the larger-than-life portraits addressing masculinity and race. Most iconic of all is the mural for No-Race Creme, which is placed on the large back wall, and commands the room with the image of a manicured hand of a woman smearing red, white and blue makeup across her cheek.

Ironically, as you exit the CUAS space, a huge billboard is visible, looming over South Halsted Street. In a real-world juxtaposition of the show’s title, the bright red advertisement is for Coca-Cola and McDonald’s new sweet-tea drink. It’s a missed opportunity for some of Noland’s wry public defacement, or perhaps just a pertinent echo of the issues Noland addresses: the relationships between commercialism, race and people with too much power. (Julia V. Hendrickson)

The Chicago Urban Art Society is at 2229 South Halsted. “Sweet Tea” is open through July 30.

[Published in Newcity, online here, and in print, June 2010].

Chicago's NPR (WBEZ, 91.5) had an interview with Noland this morning. You can listen to it here.

Proximity Magazine also has some good photographs of the exhibit here (shown below).

Title wall for the exhibit, really lovely type. Via Proximity Mag's Flickr.

--------------------------------------------------

Noland’s work is unabashedly political. He skewers celebrities, musicians, politicians and assumptions about race and gender, all with equal abandon. It’s clear that Noland was working through a lot of ideas for “Sweet Tea,” riffing on old imagery, alongside new works created with the CUAS space in mind. According to the artist, almost three-quarters of the work is new (the rest is comprised of his Obama posters and the iconic “Go Tell Mama” series). With the flexibility and sense of experimentation that portends a good future for CUAS, the directors gave Noland the opportunity to work (and occasionally sleep) in the gallery for a month prior to the opening.

Unfortunately, in “Sweet Tea,” Noland’s attempt to bring the street indoors falls flat. While the installations are charming, the handful of plywood walls, plastered with faux “weathered” posters and Noland’s signature guilty, childlike Blagos, are an ineffectual spatial experiment. Bringing Blagojevich indoors also seems unnatural; that tell-tale, hand-in-the-cookie-jar expression is most powerful when it’s unexpectedly stumbled across outside. Seen outdoors, we can picture the real Blagojevich infamously jogging (or on the lam), but indoors Blago is just running in circles, and has nowhere to go. There is simply not enough of Noland’s art to fill the huge gallery space, and the street-art atmosphere seems token when paired with Noland’s more traditionally displayed works on canvas.

What works best in the space are the bold, singular, graphic works—the intricately stenciled portraits on canvas, rich with layers of flat color, and the tongue-in-cheek advertisements for No-Race Creme. Noland’s background in design is evident, for his strength lies in icons, particularly the larger-than-life portraits addressing masculinity and race. Most iconic of all is the mural for No-Race Creme, which is placed on the large back wall, and commands the room with the image of a manicured hand of a woman smearing red, white and blue makeup across her cheek.

Ironically, as you exit the CUAS space, a huge billboard is visible, looming over South Halsted Street. In a real-world juxtaposition of the show’s title, the bright red advertisement is for Coca-Cola and McDonald’s new sweet-tea drink. It’s a missed opportunity for some of Noland’s wry public defacement, or perhaps just a pertinent echo of the issues Noland addresses: the relationships between commercialism, race and people with too much power. (Julia V. Hendrickson)

The Chicago Urban Art Society is at 2229 South Halsted. “Sweet Tea” is open through July 30.

[Published in Newcity, online here, and in print, June 2010].

--------------------------------------------------

Ray Noland's Flickr album of the show is here, and his website is CRO (Creative Rescue Organization).Chicago's NPR (WBEZ, 91.5) had an interview with Noland this morning. You can listen to it here.

Proximity Magazine also has some good photographs of the exhibit here (shown below).

MARS! (Oil).

MARS! from Joe Bichard and Jack Cunningham on Vimeo.

Oil. Think about this:

Map of Chicago with the oil

Great infographic from Info Graphic World about the implications of the disaster.

The Daily Green's got 7 Ways To Help Clean Up, some more pertinent than others.

Friday, June 11, 2010

"Mingei-sota": Guillermo Cuellar's Studio & the St. Croix Valley Pottery Tour

In early May I had the great privilege and opportunity to travel to Minnesota with my dear friend A.C. and participate in an extraordinary ceramic tradition. Each spring, a group of talented Minnesota potters around the upper St. Croix River (about an hour’s drive Northeast of Minneapolis, along the Wisconsin border) fire up their kilns and set forth a bountiful display of ceramics delights. The wares range from spare to very decorative, but are most often functional in nature—simple, basic materials, with uncomplicated glazes and clean lines—many with the influence of Japanese mingei (folk-art) aesthetics as taught by one of the founders of the pottery festival, Warren MacKenzie.

Since my own pottery roots are based in Eastern Ohio, my knowledge of pottery tends to lean towards industrially made wares (Homer Laughlin, Hall China, Vodrey Brothers, etc), as seen at the Museum of Ceramics in East Liverpool, Ohio. Thus, I was fascinated to be a small part of a new and different world of hand-made ceramics. While in Minnesota I was graciously hosted by potter Guillermo Cuellar, and his spouse, Laurie MacGregor. Guillermo Cuellar is originally from Caracas, Venezuela, but studied ceramics at Cornell College in Iowa, where he and Laurie first met in the 1970s. They moved back to Venezuela (to Turgua, southeast of Caracas), starting a family and a pottery in the early 1980s. In 1981 Warren MacKenzie held a workshop in Caracas, which is when Guillermo and he first met, and during the summers throughout 1984 to 2006 Guillermo traveled to Warren’s studio in Minnesota to work and make pottery.

Since Guillermo has studied and worked very closely with Warren MacKenzie, in order to better understand Guillermo’s work I would first like to backtrack a little bit and discuss Warren and his influences. Surprisingly enough, I was delighted to find out that this story has some Chicago and printmaking connections.

Warren MacKenzie was born in Kansas City in 1924, and his family moved to Evanston, Illinois when he was a child. He attended the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC) for painting in the early 1940s, and took printmaking and design classes with the venerable Kathleen Blackshear. Blackshear was known for her focus on teaching about the importance of looking at non-Western art as art. In 1943 Warren was drafted into the army, and as a result of his printmaking background, was directed to silkscreen instructional posters for the army.

In 1946 Warren returned to school, only to find that all of the SAIC painting classes were full. He signed up for ceramics instead, and while he did not have very good ceramics instructors, began to immerse himself in thinking about pottery. It was around this time that he and fellow students discovered Bernard Leach’s seminal text, A Potter’s Book (Faber & Faber, 1940). Inspired by Leach’s words, Warren moved to St. Paul, Minnesota in 1948 with his wife and fellow-potter, Alix, with the intention of teaching ceramics and starting his own pottery.

Bernard Leach (1887–1979) was a renowned British studio potter. Born in Hong Kong, he grew up in Japan (his grandparents were missionaries), and at age 10 moved to England. He studied etching (another printmaking connection!) at the London School of Art before returning to Japan in 1909. There, after attempting to teach printmaking, he became fascinated by ceramics. He also sparked what would become a life-long friendship with potter Shoji Hamada (1894–1978), and in 1920 the two men returned to England and founded the Leach Pottery Studio in St. Ives, Cornwall. Hamada helped Leach build the first traditional Japanese wood-fired kiln in the Western world. Hamada remained in England until 1923, when he returned to Japan to start his own studio in the town of Mashiko.

By 1948, when Warren MacKenzie graduated from SAIC, Bernard Leach was well established in his St. Ives studio, producing a tremendous output of work to keep up with the demand from his catalogues. Hoping for inspiration for their own studio, in 1949 Warren and Alix took a two-week trip to England to meet Leach, and while their work did not impress him, their dedication did, and Leach eventually invited them to return in a year’s time in order to work with him. They returned in 1950, and stayed for 2 ½ years, living in Leach’s house, studying under him and gaining a broader exposure to other British potters, as well as becoming influenced by East Asian potters such as Shoji Hamada.

In an interview Warren notes,“the pots that really interested us were the pots that people had used in their everyday life, and we began to think – I mean, whether it was ancient Greece or Africa or Europe or wherever, [that] the pots that people had used in their homes were the ones that excited us.” In 1952 Warren and Alix returned to Minnesota, filled with energy and a resolve to create a pottery studio that was more focused on hand craftsmanship rather than production for a catalogue.

By the 1970s, when Guillermo Cuellar was in college, Warren MacKenzie had become successful enough that he was appearing in Guillermo’s ceramics textbooks. As mentioned before, among many other studio and art potters from the United States, Warren held a workshop in Venezuela in the early 1980s, which Guillermo attended. Then, much like Warren’s experience with Leach, in the spring of 1984 Guillermo travelled to Minnesota—along with a few other potters—to live and work alongside Warren. Guillermo describes the experience as “more than learning about pottery, it was having a family,” absorbing information, ideas, and values.

This small group held a good-old Midwestern pottery sale at the end of the summer, representing their months of working together and having fun making pots. This sense of community and collective energy inspired Guillermo, given that it was so different from the individualistic and often-secretive mannerisms of other potters at the time, and he returned to Venezuela with the intention of repeating the experience.

Guillermo and Laurie bought property in Turgua, Venezuela in late 1984, and in 1986 he completed his studio. By 1992, as a similar group was forming back in Minneapolis, Guillermo organized the first pottery sale and festival in Turgua, starting off with a group of ten other potters and two jewelers. Guillermo and the other potters formed a co-op, Grupo Turgua, jointly inviting guest potters over the years from Venezuela and the United States who shared similar aesthetic ideas. The event, which became known as el encuentro de Turgua (Turgua’s meeting place), rapidly grew, occurring twice a year. Eventually the sales encompassed many other forms of art-making besides pottery, including photography; woodwork; drawing; and weaving. Such collective action became a source of national pride in Venezuela, often making the front pages of the national news. A publisher based in Venezuela, Ex Libris, even offered to compile a history of the Grupo Turgua, which was published in 2003.

As the political climate shifted with Hugo Chávez’ rise to power in the late 1990s and early 2000s, so, too, did the community which sustained and supported the Grupo Turgua. Eventually Guillermo and his family decided to make a change, and moved to Minnesota in 2005, returning in the winter of 2005 for one last Venezuelan pottery sale.

Now jokingly called “Mingei”-sota by pottery lovers, Minnesota was the natural settling point, of course, because Warren MacKenzie’s work and teaching over the last few decades had established a strong community that supported art and studio pottery. As Warren described in an interview, "There is something about living in Minnesota, or living in the Midwest, I think I’d say. My pots are really most at home in the Midwest, and I think there’s a number of potters who have gravitated to this area because they find it sympathetic to hand pottery."

Both potters and enthusiasts alike are drawn to the area, and a celebration of the craft is realized in the annual St. Croix Valley Pottery Tour. When I arrived in May it was going on its 18th year, with seven host potters (including Guillermo) showing a whopping total of 37 guest potters at their respective homes and studios. It was completely beautiful, and a treat to be around such a talented, passionate, and down-to-earth group.

Since can’t share everything in this essay, please do take a look at more of the photographs from the weekend, in my Flickr album, and in an album on Guillermo’s website.

(Note: Most of my information in this essay is gleaned from conversations with Guillermo, as well as a fascinating Smithsonian Archives of American Art interview with Warren MacKenzie).

Since my own pottery roots are based in Eastern Ohio, my knowledge of pottery tends to lean towards industrially made wares (Homer Laughlin, Hall China, Vodrey Brothers, etc), as seen at the Museum of Ceramics in East Liverpool, Ohio. Thus, I was fascinated to be a small part of a new and different world of hand-made ceramics. While in Minnesota I was graciously hosted by potter Guillermo Cuellar, and his spouse, Laurie MacGregor. Guillermo Cuellar is originally from Caracas, Venezuela, but studied ceramics at Cornell College in Iowa, where he and Laurie first met in the 1970s. They moved back to Venezuela (to Turgua, southeast of Caracas), starting a family and a pottery in the early 1980s. In 1981 Warren MacKenzie held a workshop in Caracas, which is when Guillermo and he first met, and during the summers throughout 1984 to 2006 Guillermo traveled to Warren’s studio in Minnesota to work and make pottery.

Guillermo Cuellar serving bowl, blue and ash glaze, 5 x 6 1/4", and teapot, matte glaze

with crackle slip, 7 x 7 1/2 x 5 1/2" as seen in his showroom.

Since Guillermo has studied and worked very closely with Warren MacKenzie, in order to better understand Guillermo’s work I would first like to backtrack a little bit and discuss Warren and his influences. Surprisingly enough, I was delighted to find out that this story has some Chicago and printmaking connections.

Warren MacKenzie was born in Kansas City in 1924, and his family moved to Evanston, Illinois when he was a child. He attended the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC) for painting in the early 1940s, and took printmaking and design classes with the venerable Kathleen Blackshear. Blackshear was known for her focus on teaching about the importance of looking at non-Western art as art. In 1943 Warren was drafted into the army, and as a result of his printmaking background, was directed to silkscreen instructional posters for the army.

In 1946 Warren returned to school, only to find that all of the SAIC painting classes were full. He signed up for ceramics instead, and while he did not have very good ceramics instructors, began to immerse himself in thinking about pottery. It was around this time that he and fellow students discovered Bernard Leach’s seminal text, A Potter’s Book (Faber & Faber, 1940). Inspired by Leach’s words, Warren moved to St. Paul, Minnesota in 1948 with his wife and fellow-potter, Alix, with the intention of teaching ceramics and starting his own pottery.

Bernard Leach (1887–1979) was a renowned British studio potter. Born in Hong Kong, he grew up in Japan (his grandparents were missionaries), and at age 10 moved to England. He studied etching (another printmaking connection!) at the London School of Art before returning to Japan in 1909. There, after attempting to teach printmaking, he became fascinated by ceramics. He also sparked what would become a life-long friendship with potter Shoji Hamada (1894–1978), and in 1920 the two men returned to England and founded the Leach Pottery Studio in St. Ives, Cornwall. Hamada helped Leach build the first traditional Japanese wood-fired kiln in the Western world. Hamada remained in England until 1923, when he returned to Japan to start his own studio in the town of Mashiko.

By 1948, when Warren MacKenzie graduated from SAIC, Bernard Leach was well established in his St. Ives studio, producing a tremendous output of work to keep up with the demand from his catalogues. Hoping for inspiration for their own studio, in 1949 Warren and Alix took a two-week trip to England to meet Leach, and while their work did not impress him, their dedication did, and Leach eventually invited them to return in a year’s time in order to work with him. They returned in 1950, and stayed for 2 ½ years, living in Leach’s house, studying under him and gaining a broader exposure to other British potters, as well as becoming influenced by East Asian potters such as Shoji Hamada.

In an interview Warren notes,“the pots that really interested us were the pots that people had used in their everyday life, and we began to think – I mean, whether it was ancient Greece or Africa or Europe or wherever, [that] the pots that people had used in their homes were the ones that excited us.” In 1952 Warren and Alix returned to Minnesota, filled with energy and a resolve to create a pottery studio that was more focused on hand craftsmanship rather than production for a catalogue.

By the 1970s, when Guillermo Cuellar was in college, Warren MacKenzie had become successful enough that he was appearing in Guillermo’s ceramics textbooks. As mentioned before, among many other studio and art potters from the United States, Warren held a workshop in Venezuela in the early 1980s, which Guillermo attended. Then, much like Warren’s experience with Leach, in the spring of 1984 Guillermo travelled to Minnesota—along with a few other potters—to live and work alongside Warren. Guillermo describes the experience as “more than learning about pottery, it was having a family,” absorbing information, ideas, and values.

This small group held a good-old Midwestern pottery sale at the end of the summer, representing their months of working together and having fun making pots. This sense of community and collective energy inspired Guillermo, given that it was so different from the individualistic and often-secretive mannerisms of other potters at the time, and he returned to Venezuela with the intention of repeating the experience.

Guillermo and Laurie bought property in Turgua, Venezuela in late 1984, and in 1986 he completed his studio. By 1992, as a similar group was forming back in Minneapolis, Guillermo organized the first pottery sale and festival in Turgua, starting off with a group of ten other potters and two jewelers. Guillermo and the other potters formed a co-op, Grupo Turgua, jointly inviting guest potters over the years from Venezuela and the United States who shared similar aesthetic ideas. The event, which became known as el encuentro de Turgua (Turgua’s meeting place), rapidly grew, occurring twice a year. Eventually the sales encompassed many other forms of art-making besides pottery, including photography; woodwork; drawing; and weaving. Such collective action became a source of national pride in Venezuela, often making the front pages of the national news. A publisher based in Venezuela, Ex Libris, even offered to compile a history of the Grupo Turgua, which was published in 2003.

As the political climate shifted with Hugo Chávez’ rise to power in the late 1990s and early 2000s, so, too, did the community which sustained and supported the Grupo Turgua. Eventually Guillermo and his family decided to make a change, and moved to Minnesota in 2005, returning in the winter of 2005 for one last Venezuelan pottery sale.

Now jokingly called “Mingei”-sota by pottery lovers, Minnesota was the natural settling point, of course, because Warren MacKenzie’s work and teaching over the last few decades had established a strong community that supported art and studio pottery. As Warren described in an interview, "There is something about living in Minnesota, or living in the Midwest, I think I’d say. My pots are really most at home in the Midwest, and I think there’s a number of potters who have gravitated to this area because they find it sympathetic to hand pottery."

Both potters and enthusiasts alike are drawn to the area, and a celebration of the craft is realized in the annual St. Croix Valley Pottery Tour. When I arrived in May it was going on its 18th year, with seven host potters (including Guillermo) showing a whopping total of 37 guest potters at their respective homes and studios. It was completely beautiful, and a treat to be around such a talented, passionate, and down-to-earth group.

Conversations amidst pottery, (L to R) Guillermo Cuellar, potter Dick Cooter, artist Debbie Cooter.

(L to R) A. Cuellar, C. Cuellar, potter Ryan Strobel.

Guillermo's studio and wheel.

Since can’t share everything in this essay, please do take a look at more of the photographs from the weekend, in my Flickr album, and in an album on Guillermo’s website.

(Note: Most of my information in this essay is gleaned from conversations with Guillermo, as well as a fascinating Smithsonian Archives of American Art interview with Warren MacKenzie).

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)